I step outside to golden Aspen orbs dancing against a blue sky, and the air is crisp on my skin. The Aspen trees are flanked by the arching dome of The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart on the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. The white limestone walls of the Cathedral, the speckled leaves tumbling towards winter, the uniformity of the awakening blue sky offer an acute sensation of clarity — clarity of mind, of purpose — in that precise way only early morning can lend. It was the same clarity I read on a graffitied wall the day before while walking Richmond’s red brick central streets, painted alongside an image of Harriet Tubman’s outstretched hand: Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter.

Lately the question of silence has been a constant reprimand. Have you “spoken” out against the war? For the “right” side?

Have you used the right words? Have you taken risks with your marching fingers across a raging screen?

I sit on a hanging swing affixed to the porch of the Airbnb where I’ve spent the weekend at a conference and wait for my ride. I am almost never alone in the early morning Sunday light. My kids are several hundred miles away. The VCU campus is silent. I let the rays of sunlight dance across my eyelids and conjure the questions posed by documentary artist Sayre Quevedo during his talk the day before at the 2023 Resonate Podcast Festival:

When am I happy and when am i sad?

What is the difference?

What do i need to know to stay alive?

What is true in the world?

My reverie is interrupted by the vibration of my phone. I think it’s the Uber but no, it’s my friend Maya, DMing me from underneath the Iron Dome, 5,939 miles away.

“Such a limited view of the middle eastern conflict is what is putting so many intelligent people like yourself on the wrong side of history,” she writes. “It’s so tragic, really.”

The breeze rustles the leaves and she goes on. “How many Israelis have you spoken to before you posted your ‘moral’ stance?”

I have been expecting this, but my heart accelerates nonetheless. I say to myself i’m not going to deal with this right now but I’m already crafting a response in my mind.

How many Palestinians did you speak to before deciding that they deserve to die?

But I don’t respond. I try to hold on to the shimmering leaves, to this breath of silence, to the slowing of my heart in my chest.

Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter.

Maya is speaking her truth, a version of the truth, the thing that she needs to say in order to stay alive.

She is angry about an article I had shared the day before, a piece I edited on Palestinian solidarity in Latin America and the bloody history of Israeli military support for the region’s most decadent military regimes.

“This is not Latin America” Maya writes, and sure, she’s not wrong.

But Latin America is what I know, and that’s where I choose to lift my voice. Its lands and stories have been my sustaining thread.

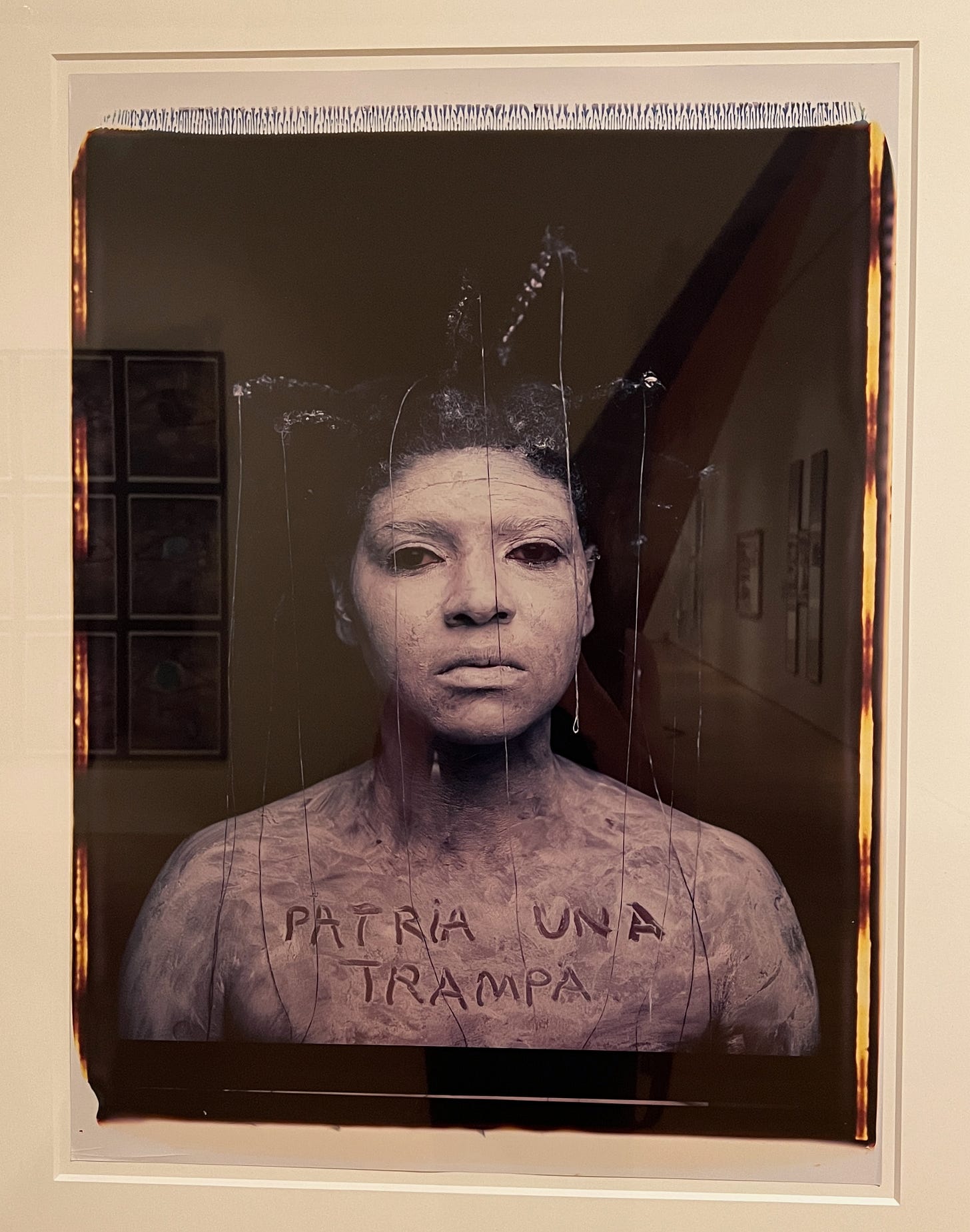

On the way to the airport I think about a piece of artwork I saw recently by the Cuban artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons at the Brooklyn Museum. It’s a photograph of the artist, her body painted in the white color of Orisha Obatalá, creator of the world and of humanity. Obatalá is the source of all that is pure, wise, and compassionate. The artist’s hair is plaited into braids that stand upright, and from each braid hangs a thread; together the threads encircle her face in a kind of enclosure. Her gaze is defiant. As a viewer I am left with the impression that if she were to blink, a tear might be relinquished from her eye.

On her chest, letters are etched out of the white paint:

PATRIA UNA TRAMPA

Homeland is a trap.

Much of Campos-Pons’ work is inspired by the scholar Homi Bhabha’s theory of the Third Space, or the “in-betweenness” of cultural identities shaped by migration and coloniality. The curator Okwui Enwezor describes her work as a “series of conjunctions—roots and routes, origin, and displacement” that trace the fragments of her movement through time and space. They are fragments rooted to an ancestral core, one that sustains a vital connection to her mother’s ancestral lineage, often represented through roots of hair.

In an accompanying image, Campos-Pons’ eyes are closed. The paint on her body is thick and drips down her neck. Inscribed on her chest:

IDENTITY COULD BE A TRAGEDY

“The body is a metaphor, this is not a self-portrait,” Campos-Pons has said of the series. “The personal is a vehicle to narrate a more complex story.” I think about how the personal is distorted and flattened on a screen, about all the noise that is behind the things we share or don’t share. About how we are reduced to single identities, gestures, statements.

Absences.

“My work over the past 35 years addresses post-coloniality and the complexities that entangle the narratives, connections, and mutual dependency of the North and the South,” Campos-Pons says. “My work speaks to an ancestral knowledge and tradition to give a voice to the darkest narratives with grace and aesthetic elegance.”

In the Gaza war, the complexities and dependencies of North and South are hyper concentrated upon one tortured strip of land. “From the land to the sea” is read as a call for liberation and simultaneously as an invocation of annihilation. Lives are weighed, cast off, elevated, extinguished in a single

command,

Headline

qualifier,

like,

share.

A friend of mine who works at a prestigious news podcast says he squabbled with his superiors over the question of inserting the word “people” after “Palestinian” when referencing fatalities. “People” was already affixed to the Israeli death toll, he’s told, and repetition breaks up the radio flow.

Is the omission a form of silencing, of erasure? Or is it merely an aesthetic choice? Campos-Pons tells us that our aesthetic choices matter, that we must find ways to narrate our darkest narratives with grace.

When Rashida Tlaib—the only Palestinian American in Congress—is censured for invoking her ancestral territory, from the river to the sea, it is indeed erasure. It is wildly public foreclosure of the idea that we should be exposed to a non-dominant voice.

“I can’t believe I have to say this,” Tlaib said on the House floor, “but the Palestinian people are not disposable.” What she named “an aspirational call for freedom, human rights and peaceful coexistence” is deemed by democrats and republicans alike as “promoting false narratives.”

Patria is, indeed, a trap.

Last month, I saw an exhibition of the works of Vietnamese artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen at the New Museum in Manhattan. Titled “Radiant Remembrance,” the show featured film and videography projects that deal with themes of displacement, animism, and material memory. At one end of the gallery hung a reconfigured bell made from an unexploded M117 bomb that had been dropped from an American plane during the Vietnam war. When struck with a mallet, the ordnance-turned bell produces a vibration at 432 hertz, a frequency believed to resonate harmoniously with the human body. Suspended from a supporting structure representing elements of traditional Vietnamese pagodas, the artwork and its reverberation echo Vietnam’s rich and complex history; an embodied symbol of sonic repair.

In the four-way immersive video installation “The Specter of Ancestors Becoming,” Nguyen explores the legacy of tirailleurs, soldiers from the French colonial territories of Senegal and Morocco who were enlisted to fight Viet Minh anticolonial uprisings during the First Indochina War (1946 - 1954). The project was made in collaboration with descendants of tirailleurs in West Africa and draws from real and imagined letters to bring to life dialogues with deceased ancestors on themes of exile, estrangement, and repatriation.

In one scene, a young Senegalese-Vietnamese man argues with his father in what appears to be the father’s ornate office in Dakar. The father has refused to meet his granddaughter because she has been christened with the name of the son’s Vietnamese mother, a woman he has never known. The son was raised with no knowledge of his biological mother, made to believe that he descends from a Senegalese maternal line. The subtle but elegant curves of his eyes betray a deeper truth. The exhibition is curated so that the viewer is positioned in the middle of four surrounding screens, each depicting a different scene or perspective; that of the father; that of the son; two figures practicing Võ Vi Nam, a traditional Vietnamese martial art; and that of a narrator who reads the dialogue as if from a letter, speaking for the father and for the son. Here Nguyen complicates the question of narrative, obscuring who is speaker, who is letter-writer, who is the conveyor of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

The mother, of course, is absent. She is never named, never seen.

I think about the question of naming when May sends me a New York Times op-ed about the silent sympathies surrounding the Israeli hostages that were taken by Hamas. When I come across their faces affixed to the New York City streets, some defaced and torn apart.

What about the faces of the nearly 7,000 women and children that have been killed in Gaza, who never asked for this war?

Or, indeed, the faces of the dozens of farmworkers from Thailand who were killed or kidnapped by Hamas, who toiled in fields that were not protected by Israel’s Iron Dome, who were housed in caravans and containers that were not equipped with the anti-rocket shelters that are standard in Israeli homes.

In a recent Daily episode, journalist David Shipler tells Michael Barbaro that Palestinians and Israelis alike are imprisoned by their history, unable to see beyond or through the origin stories that have shaped their lives and adversaries.

Are we not all imprisoned, to some degree, by the stories we tell ourselves about who we are? Is Campos-Pons correct in contending that the motherland is a trap, that identity is tragedy? And if so, how do we find our way out of the narratives that bind and sometimes condemn us?

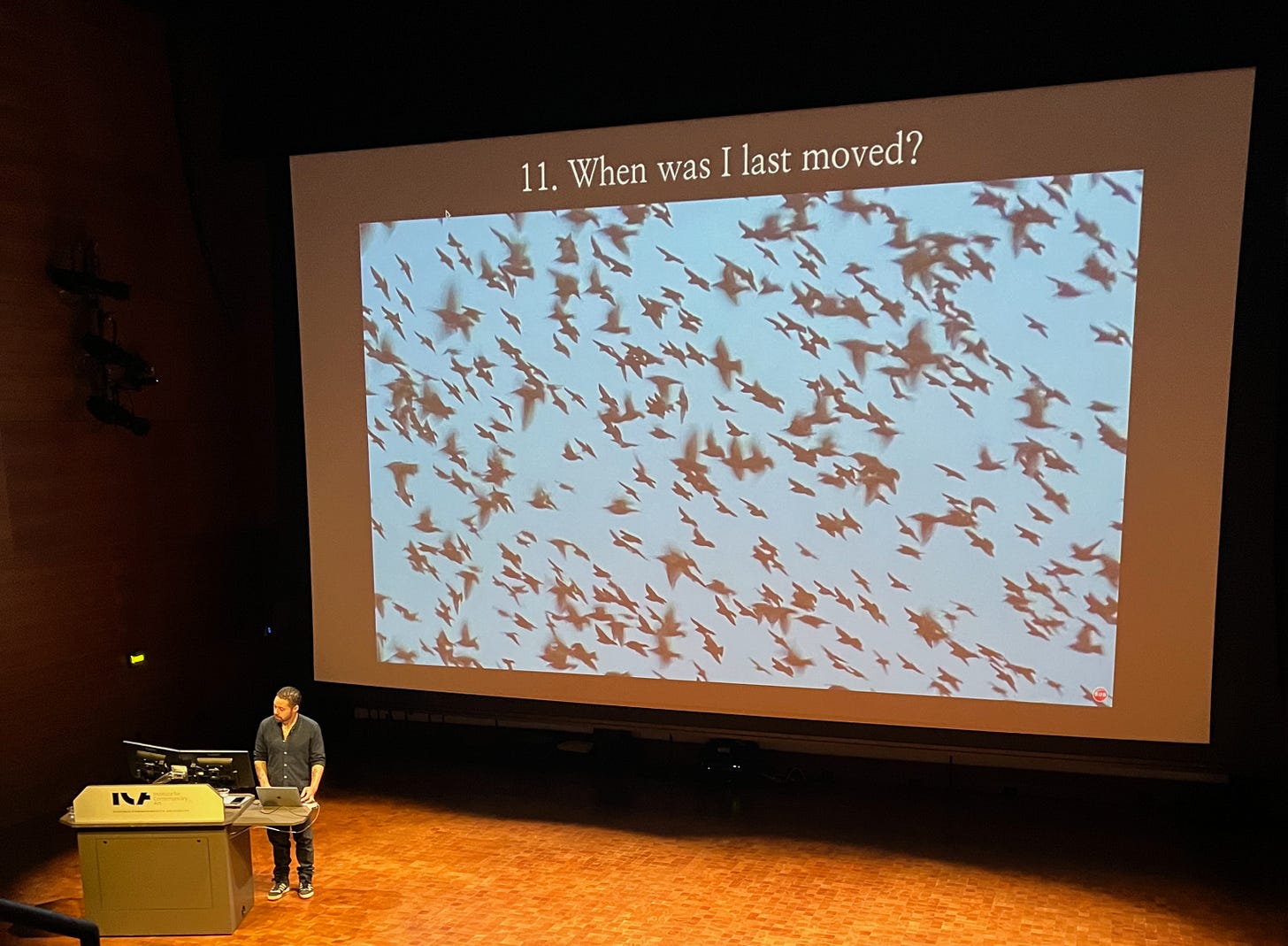

During his talk at the Resonate festival, the artist Sayre Quevedo shared an image of a group of birds in flight, their movements murmurating across the screen, under the question:

When was I last moved?

During the 2-day festival, Sayre was the only presenter to mention the ongoing war in Gaza, among a group of some 200 journalists, aside from a nod at the end from the organizers on the at least 37 journalists—32 Palestinian—that have been killed so far in the war.

Are we allowed to be moved in times of polarization and warfare? If we share small moments of joy—with each other, on social media—are we disrespecting the victims of an ongoing campaign of destruction? Can we concede that the Palestinian people, besieged by occupation, bombardment, ground invasion still must seek moments of laughter, of joy, of hope in the context of war?

Is it not conmoción, the feeling of being stirred, moved, shaken, rocked, that reminds us that we are alive?

All questions come from a lineage, says Sayre (and Campos-Pons and Nyugen and Homi Bhabha’). So perhaps our task is to trace that lineage, sit with the parts that are painful or unsavory, celebrate the parts that are happy and true, and ask ourselves if the survival of our own lineage has stood upon the erasure or extinguishment of another. Can we look upon our alleged adversaries with grace? Can we hold our darkest narratives with tenderness and care?

This is not to simplify a profoundly complex and harrowing conflict, especially for those who seek survival daily underneath its weight. But for those of us that are far away, who struggle to delineate the shapes and contours of solidarity: our words, our gestures, our choices matter. Freedom, says Toni Morrison, is about “being able to choose which things you want to be responsible for.”

I have decided to assemble a diary—in my mind, perhaps on paper, perhaps only in the fluttering of aspen leaves and the dance of sunlight on my eyelids—of moments that move me, that give me pause, that suspend the flow of breath through my lungs.

Meaning is made from those moments, they are what we need to stay alive.

Thank you for beautifully capturing so much of the complexity and pain of this moment. I have been grappling with this: “for those of us that are far away, who struggle to delineate the shapes and contours of solidarity: our words, our gestures, our choices matter”