There are days when the gravity

Of all that needs mending in my life—

Presses down on my larynx

Sits a heavy tumor in my belly

Gnaws at my reasoning like a crisis…

Just over decade ago, I found myself standing on the median on Avenida Blanco Galindo, near central Cochabamba, at dusk. I was attempting to make my way across several lanes of rush-hour traffic towards our old apartment on Avenida Garcilazo de la Vega when my cell phone rang. It was my sister.

I still remember the purple hue of the sky above Mt. Tunari in the distance, the smell of exhaust fumes as trufis stopped haphazardly to drop off and load passengers along the edge of the roadway. That was before we moved to Tiquipaya, before my girls were born, back when P and I shared our first apartment together below our friends Aliya and Chelo and their newborn daughter. The house was a mess, literally coming apart at the seams, the garden a chorus of potted plants and debris and chipped tiles.

My god, we were so happy there.

My sister is telling me that there’s been an accident. I can’t grasp all the details but it’s about my uncle, my mom’s brother, he’s had a fall.

I’m still standing on the median, trying to block out the noise with my hands cupped over my ears. This is one of those moments when the consequences of choosing to build a life 4,695 miles from home start to sink in. My sister didn’t care much for my uncle—she never felt welcomed by my mom’s family, her step family—but there’s worry in her voice.

“He’s paralyzed,” she says, as my foot steps off the median into the swell of traffic, momentarily paused. “He’ll probably never walk again.”

Days when I have run out of faces to keep up appearances

I feel like an ellipsis. Waiting for the good to come

When the inner self goes down on its knees asking for life to

come to a halt

I started writing after that. I felt this need to show up in some way for my uncle, Uncle Robin, who wrapped everyone around him up with joy. Nieces to pieces he always called me, leaving implied the beginning of the refrain: I love my…

Even in paralysis, Robin didn’t lose his gusto, his optimism, in some tragically comic way thrilled that he had an excuse to spend his life glued to the TV. Robin was a simple man, never driven by ambition or ego. He lived for that gig, for that drink with a buddy at the end of a workday, for that phone call where he would go on and on and you could never get him off the line because he’d remember one more thing he wanted to say…

I set to work writing a story for Robin, the story of a mystical journey I had recently taken into the Apolobamba Mountains with my biological father Lee, a man I had not known in childhood. Robin lived on the memories of his long ago travels, regaling me continually with the story of being sent by my grandfather to track down my mother on an island off the coast of Brazil in the mid-1970s, after she had bailed on law school and moved to South America as a vagabond hippy who sold potato-sack pants on the side of the road.

My story for Robin—a delightful, bewildering, emotionally painful journey that involved levitating dwarfs and a family of transcendent Kallawaya healers tucked away in one of the most remote mountain chains on earth—has sat unfinished on my desktop all these years. I haven’t been able to finish Lee’s story, even after Lee himself passed away in the winter of 2017, in part because I was plagued by the fear that I could never be a writer. Not in the way my cousin Alice is, Lee’s niece, or in the way that would please my other father, the one that raised me, my sister’s dad.

In recent years, Uncle Robin’s life had whittled away gradually, atrophied like the muscles in his body that would never again animate to hold his once sinewy frame. I am built like him, I realize now, long and lanky and mildly awkward. In the early years after his accident there was some hope he would recover partial mobility—and indeed there was a time when he could stand, move one hand, even inch his body forward—but the physical therapy petered out as did my aunt’s drive to motivate him to live a semblance of a life, and he retreated to a medical bed, behind a screen, his days measured by sports games and his favorite shows and a single cigarette on the front porch in the afternoon.

The last time I saw Robin it was a torturous affair to get him out of bed. He joined us on the porch on an August afternoon, my kids and the dogs running circles around his wheelchair. That stubborn enthusiasm was still in his voice, though greatly diminished, and he asked about P and about Bolivia as he always, always did. But within minutes he could not sustain his clenched and debilitated body upright any longer and asked to be taken back to bed.

Uncle Robin passed away two weeks ago, November 27, after being hospitalized for pneumonia. It appears that he passed in his sleep, without struggle, and hopefully without pain. My mom says that perhaps it's better this way; better he didn’t suffer further, because what he had was not a life. We all know that his life was taken from him on that day ten years ago, when he fell down the back steps at the house on Dahlia and severed some consequential filament of communication between his spine and the rest of his body.

Te quiero, tío. And I will go on writing, even though my story for you never found its way on the page.

Then I remember that I am the very personification of God

Brain wired to keep rewiring itself towards redemption

A body that has taught itself how to hold on to life the way pain

Holds on to women

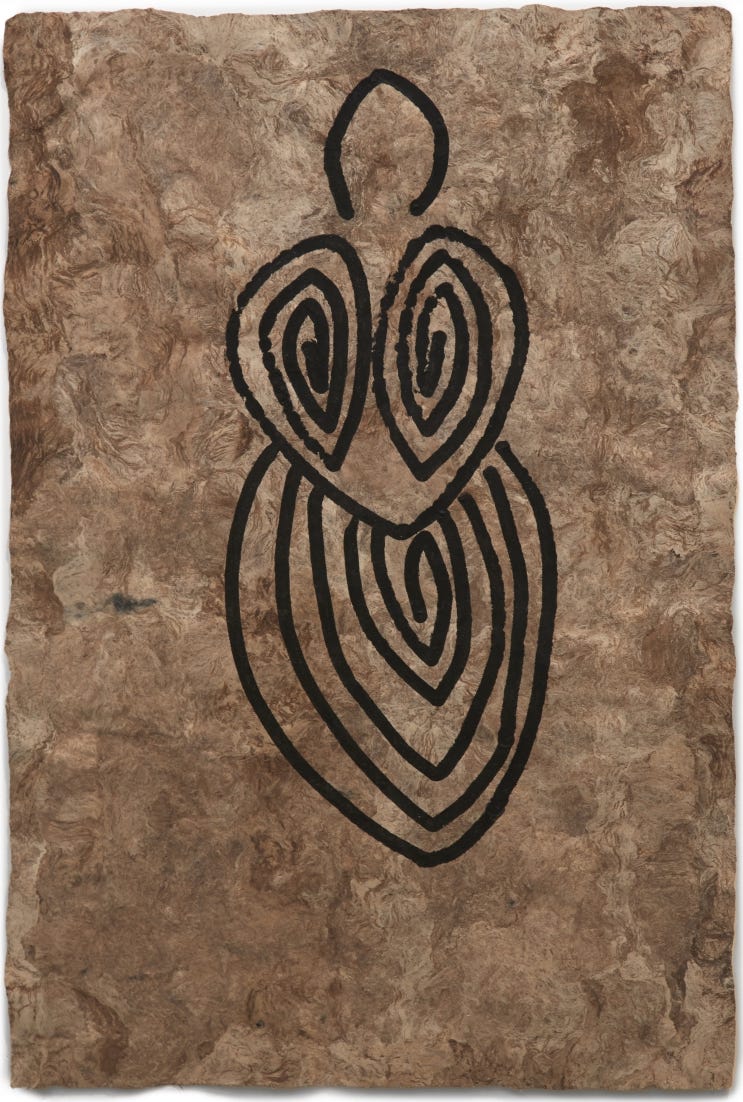

A year after moving back to the United States I got a tattoo on my upper inner arm of a drawing by the Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta. Mendieta is best known for her Silueta Series (1973 - 1978), a collection of more than 200 earth-body works in which the artist carved, burned, or molded the outline of her body into dispersed landscapes across Iowa and Mexico. Nearly all of them ephemeral, the works were an ongoing conversation between Mendieta and the territories that both held and rejected her; an effort, in her own words, to “return to the maternal source.”

In a paper I wrote about Mendieta and the Central American Indigenous feminist notion of cuerpo-territorio,1 body-territory, I wrote the following of Mendieta’s work: “Drawing from Taíno and Afro-descendent ritual practices and blended with genealogies of women of color feminism, Mendieta reclaims the body as both battleground and ancestral territory, inserting it into terrains of dispossession and dissolving the boundary between heteropatriarchal violence against the female and feminized body and colonial violence against the earth.”

The image tattooed on my arm is a serpentine feminine figure Mendieta called El Laberinto de Venus. It is, I think, an effort to locate my own body in recurring experiences of dislocation,2 and to link that search to wider struggles over land and territory. In Bolivia, my home of 13 years and the place that has shaped my adult life, I am an outsider; externally, at least, I don’t belong. In New Mexico and Colorado, the places where I was born and raised, respectively, I experience a kind of internal dissonance, manifested in a deep connection to the landscape but a sense, socioculturally, that I am out of place.

In Brooklyn, where I currently reside, I am just another transplant from far away, trying to survive, uprooted from lineage and affective networks of care. Alone in a box on an island, surrounded by millions of people.

Mendieta’s work is unsettling and transfixing, a practice that the scholar Jens Andermann describes as “a persistent and even obsessive tendency to want to suture, through the body that becomes earth and vice versa, the rootlessness that encapsulates the body in its condition of exile.”3 Mendieta was displaced from Cuba to Iowa in 1961 at the age of 12, part of the notorious Operation Peter Pan that relocated some 1400 unaccompanied children from Cuba to the United States in a two-year period in the wake of the Cuban revolution. As she came of age in the unwelcoming terrain of the Midwest, Mendieta began to see herself for the first time as “something other than white,”4 reshaping her conceptualization of self in the here and there, empire and birthplace, in which movement across territory also signaled movement in the ways in which her body was read and valued. Recalling Judith Butler’s matrix of “bodies that matter,”5 Mendieta was relocated in space and time from an elite and politically important family in Cuba to the United States of the 1960s, where she and her sister were viewed as “abject creatures against whom the white subjects forged their Americanness.”6

While it’s tempting to read Mendieta’s art in the key of exile, much important scholarship has shown that her work communicates deeper layers of deterritorialization and “othering,” signaling what Caren Kaplan refers to as "the displacement of identities, persons, and meanings that is endemic to the postmodern world system."7 Embracing the condition of “other,” Mendieta was able to shine a spotlight on the everyday violences that shape perceptions of women, and especially women of color, in U.S. society. In her Silueta Series, Mendieta enacted a complex material dialogue with themes of racialization, gendering, displacement, and return through the placement / removal / disappearance of her body in territories of dispossession, an effort, she said, to “re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe.”

The Labyrinth of Venus symbol on my arm signals my own practice of suturing or repair—naturally on a level far less significant than that embodied by Ana’s own experience and body of work. It is a symbol of finding my footing outside of Bolivia, a place that shaped and defined my life for so long, of carrying her lands and stories with me, of building a life of meaning and intention in the cycle of “return.” Writing, like Mendieta’s earth-body transgressions, is a practice of picking up the pieces, of making myself whole.

Tragically, Ana’s own project of fullness was violently and horrifyingly cut short. In 1985, the year of my birth, she was pushed out of the window of her Greenwich Village apartment by her husband, the sculptor Carl Andre, just as public recognition of her work was gaining force.

I’m reminded of why self-love will never go out of fashion

Because life is fucking hard

But my God, aren’t we god?

When I first moved back to the United States in my mid-30s, I felt like an infant. I got lost on the subway, even though I had lived in New York during my college years. I had no idea how to navigate things like health insurance, conversations in English about my former life, the New York City public school system for my kids. I was consumed by the fear of failure, fear of not finding a job, fear of not being able to support my non-English speaking family.

Two and a half years later, I am still consumed by these fears.

One day not long ago I had coffee with my friend Raiane, who is from Brazil, and I asked her if she ever thought about moving “home.”

Raiane’s response was clear and considered. “I feel safer here,” she said.

What is safety, I thought, from my perch with fear. Like Raiane, I do experience a sense of physical safety —in the way I inhabit my material body—in New York. In Bolivia, I felt I had to be careful about the way I dressed, about blending in and not showing too much skin, about how I could be perceived as a foreign woman in different settings. In New York, I must admit, it has been liberating to walk out the door and realize that quite literally nobody cares about the way I dress or walk or (this is a real thing) ride my bike through the city streets with my arms stretched to the sky, earbuds in, singing aloud at full frequency to the music in my ears.

But as a mother in the United States, I worry about gun violence in schools, I worry about our limited access to health care, I worry about making the rent every month. I worry, too—agonizingly, irrationally, no matter how hard I try to push the thoughts away—that the full and nourishing years I spent in South America are construed here as lost years on the gut-punching path of “getting ahead” and building a career.

I worry as my girls’ Quechua-inflected Spanish gives way to English, as “Bolivia” becomes a story, a legend, a place occupied by dreams and faint outlines and los abuelos who we talk about but whom they don’t really know.

I was recently assigned to write an article for a US-based Spanish-language outlet on migratory grief: what it is, how to identify it, and tips for managing its effects. Without meaning to, I have found so much of my own experience articulated in this concept, one that we should be grappling with as a society far more more freely. In general, U.S. culture is profoundly deficient when it comes to traditions and practices of coping with grief.

I have learned that in the field of psychology, grief is not defined by death, as we commonly associate the term, but by loss. In life, we are losing and gaining things all the time; not infrequently, therefore, we move through sensations of grief. But the grief we must make space for is the kind that doesn’t move, the kind that bears down on our bodies and burdens the spirit. It is a feeling so often experienced as lonely, isolating, when in fact grief is one of the most universal facets of our shared humanity. It is “the commons of the soul” according to the psychotherapist and writer Francis Weller, author of the book The Wild Edge of Sorrow.

“Where there is sorrow, there is holy ground,” Weller writes by way of introduction to his book, quoting Oscar Wilde, inviting readers to reimagine our attunement to grief as sacred and essential terrain.

I think it is perhaps rather presumptuous to call myself a migrant, but I most certainly identify with aspects of migratory grief: feelings of anxiety and irritability, an inability to move on, difficulty making life decisions or following through on projects, constantly comparing one’s new place of residence with “home.”

The Spanish psychologist Valentín González Calvo describes migratory grief as partial, recurrent, and multiple; the loss of many things—including your sense of self—that is not definitive and can come in waves. It is characterized by the feeling of being trapped in limbo between two places, two cultures, two languages, two social networks, two versions of past and present. Furthermore, migratory grief is transgenerational, becoming a defining element of the family story and identity.

While doing research for the article I came to this line, so simple, so obvious, that stopped me in my tracks: “Todas las pérdidas significativas tienen sus duelo y todos los duelos tienen que ser elaborados. Si el proceso de elaboración del duelo es ignorado, retrasado, demorado... aparecen las complicaciones.”

All significant losses are accompanied by grief, and all grief needs to be processed. If the process of grief elaboration is ignored, postponed, or delayed.. complications emerge.

Pero claro, I thought. We are all bodies carrying around our unelaborated grief, not knowing how to process it, ashamed of its effects, untethered from the community support mechanisms that can aid us in recognizing and holding our grief for what it is: an indelible sign that we feel, that we love, that we exist. That our existence and our pain are worthy.

In a conversation with Anderson Cooper for his podcast on grief All There Is, Weller says our relationship with grief is not about resolution or “moving on.” It’s about making space:

What grief work does is it has a way of deepening our capacity to hold sorrow, to hold suffering. James Hillman, one of my primary teachers, said that the issues are rarely about resolution. We're not here to resolve our issues. The issue is about spaciousness. How much can I hold? How much can I allow in to touch me? For most of us, because of our traumas and our grief, that aperture has become so small that we barely register the sorrows of the world. We barely let them in.

Coming back to my conversation with Raiane, I realize that safety—emotional safety— is also about giving room to my grief, naming it, letting it in.

~I grieve for my life and home in Bolivia—what her territories, traditions, and affective networks have been to me, have given me, will continue to give, in one form or another.

~I grieve for my girls, for their loss of language and connection to the place that brought them into the world. I grieve for my inability—at least for now— to keep that connection alive in the way I would like it to be sustained.

~I grieve for my uncle, for the years of life that were taken from him by disability, and by a healthcare system that neglected to provide the care that could have added meaningful years to his life.

~I grieve for Doña Fanny, my beloved homestay mamá who we lost in August, a deeply loyal friend and mentor and mother figure to me over a period of 16 years.

~I grieve for my dear friend Mimi, who was hit by a car in a hit-and-run on the street in Brooklyn on August 14, 2022. Brilliant, irreverent Mimi who is here but not here, condemned to a long-term care facility with permanent brain damage that will never heal.

~I grieve for our giant puppy, Chaski, the messenger, who brought us joy and laughter during the pandemic months, hit by a car and killed in Cochabamba in October of last year, while we were 4,000 miles away.

~I grieve for Anita, only 18 years old, who we first met as a joyful, creative, vibrant little girl. Anita the artist, Anita beloved companion to my girls, taken from us by an untimely stroke and by medical negligence and malpractice in Cochabamba on September 5, 2022, just days after we sat together in her sunshine-soaked kitchen in Tiquipaya, under Mt. Illimani’s watchful gaze, just across the road from where my daughter was born.

~I grieve for the death and loss and destruction that seems to be mounting around us, within us. I grieve for Gaza, I grieve for Gaza.

I grieve.

What is lineage, writes the poet Laureate Ada Limón in her sublime, heart-wrenching poem “The Hurting Kind,” if not a gold thread of pride and guilt?

She continues:

I have always been too sensitive, a weeper

From a long line of weepers.

I am the hurting kind. I keep searching for proof.

I, too, am the hurting kind. And I’m tired of apologizing for my pain.

The people listed here are my golden thread, all integral fragments of my lineage in different ways. And so I sit with them from Brooklyn in our garden in Bolivia, under the jacarandá and chillijchi trees. I make room for them in the soft garden of my soul. Ana Mendieta’s Labyrinth of Venus, like some kind of metonymic map etched into my skin, will show me the way.

Author’s note:

The poetry fragments that open each section of this essay are by Ama Asantewa Diaka, in her poem “Mirror Mirror.” Her brilliant poetry collection is Woman, Eat me Whole.

I am grateful to all the poets, writers, and healers that have brought me solace and accompaniment in recent weeks, including Ama Asantewa Diaka, Ada Limón, Joy Harjo, Abraham Verghese, and Teju Cole.

A special thanks to my friend Sarah Byrden of Elemental Self, who helped me work through some of these sentiments in a virtual winter retreat.

Accredited to the Maya-Xinka comunitarian feminist Lorena Cabnal, the concept of body-territory is part of a tradition of Indigenous women land defenders organizing against logics of extraction and dispossession of both territory and feminized and dissident bodies. It is based on the notion that the (collective) body is the first territory and site of original accumulation.

I have of course never experienced forced dispossession or displacement of the kind imposed upon people, particularly women, in processes of warfare, natural disaster, colonization, and conflict of diverse forms. I speak here of my own personal experience and process of seeking a place of belonging.

Andermann, Jens. “Cuerpo fuera del Paisaje: la Geopolítica de Ana Mendieta.” Tierras en Trance: Arte y Naturaleza Después del paisaje. Ediciones / metales pesados, 2018, pp. 323-336. Translation mine. (327)

Alvarado, Leticia. “‘…Towards a Personal Will to Continue Being “Other”’: Ana Mendieta’s Abject Performances.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2015, pp. 65–85. (68)

See Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” Routledge, 1993.

Alvarado, 68.

Quoted in Blocker, Jane. Where Is Ana Mendieta?: Identity, Performativity, and Exile. Duke University Press, 1999. (58)

Thank you for this beauty, this moving insight and insightful movement, this grieving healing that so many of us need so much more of. I feel you—and look forward to grieving and laughing together under the chillijchi and jacarandá.

Thank you for putting these beautiful words to your grief- I found solace this morning in reading and re-reading